Variations on Nostalgia – Boris Berman Plays Brahms and Silvestrov

In recent months, the 85-year-old Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov has received the world’s attention more than ever due to the ongoing war. Silvestrov’s piano music covers more than half a century, and it would be hard to find a better proponent for it than the composer’s longtime friend Boris Berman, whose coming album offers a panorama of the composer’s evolution. Berman has also just released a new Brahms album – and feels an affinity between the two composers.

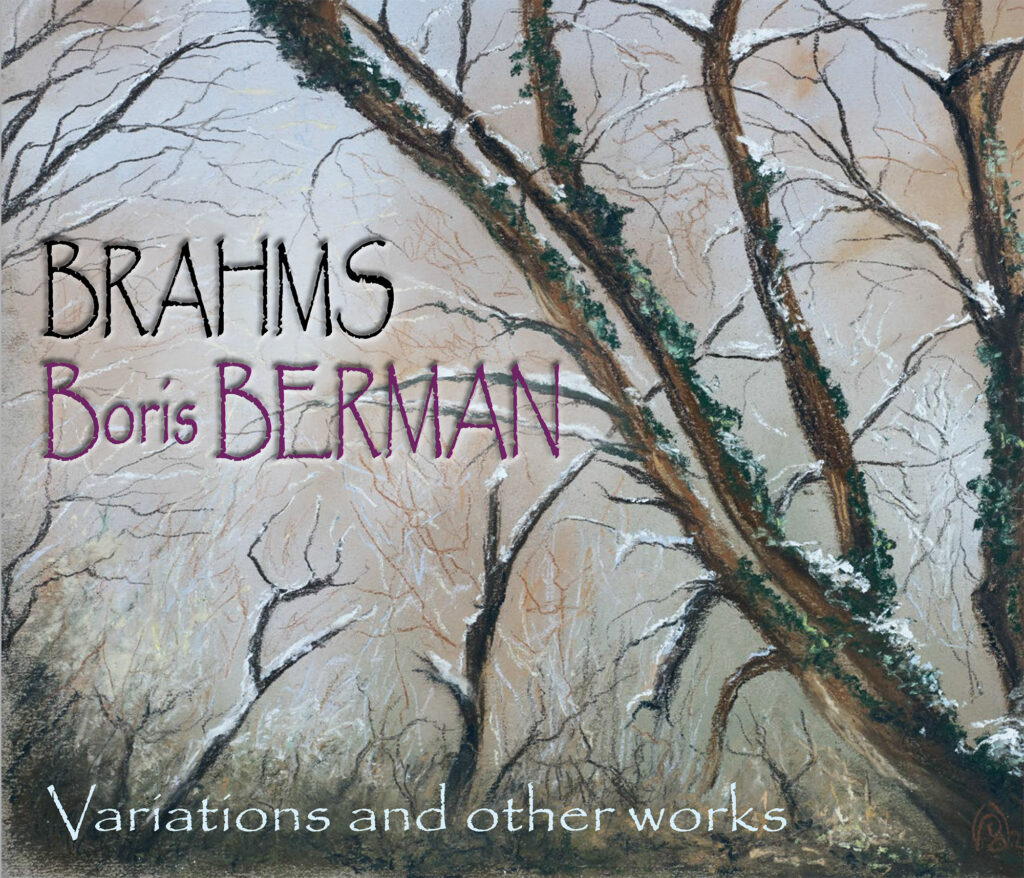

In addition to being an active performer and dedicated teacher of international stature, Boris Berman has a very rich discography. One of his most noted recordings is of Prokofiev’s complete solo piano works (Chandos), a task which he was the first pianist ever to undertake. He has also released recitals of music by Scriabin, Shostakovich, Debussy, Stravinsky, Schnittke, Cage – even, quite unexpectedly, a recording of Scott Joplin’s Ragtimes (Ottavo). Recently, Berman has recorded both solo and chamber music by Brahms for the French label Le Palais des Dégustateurs. Piano Street met Boris Berman at the Cremona Musica exhibition, where he presented a new Brahms solo album and a double album portrait of the Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov, due for release in November.

Brahms: Variations and Other Works

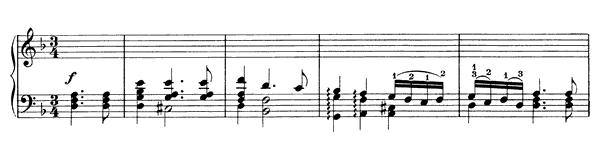

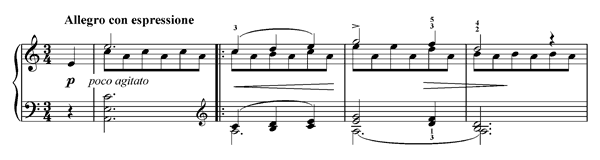

While Berman’s previous Brahms double album focused on the complete Klavierstücke (Opp. 76 to 119), the current release features more rarely performed works, such as the two variation sets Op. 21, the arrangement for the left hand of Bach’s Chaconne in D minor, and the recently discovered Albumblatt (for which Berman uses the Piano Street Urtext Edition).

Variations on an Original Theme Op. 21 No. 1

Variations on a Hungarian Song Op. 21 No. 2

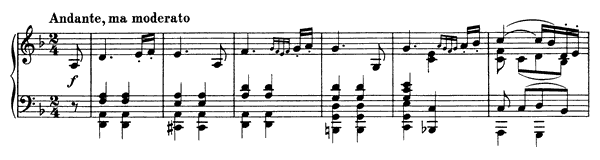

Study 5 – after a Chaconne by Bach

– The theme of your Brahms recital could be summed up as ‘Variation and Transcription’. In fact, the transcriptions on the program (The slow movement of Brahms’s own String Sextet op. 18, and Bach’s Chaconne for Solo Violin) are also variation works. What did the concept of variation mean to Brahms?

– The form of variations, and even more so, the principle of variation were very important for Brahms. It was observed by no lesser musician than Arnold Schoenberg. In his lecture “Brahms the Progressive” Schoenberg labeled Brahms’s compositional technique as “developing variation”. Working on his variation sets one observes the inventiveness of melodic variations and embellishment, as well as his frequent adherence to the Baroque practice of basing variations on an unchanged bass line of the theme. In a letter to a music critic he wrote: “To me the bass is holy, it is the firm ground on which I then build my stories.” This explains Brahms’s fascination with Bach’s Chaconne.

– Brahms’s transcription of Bach’s Chaconne has been described as “faithful to the point of severity.” Apparently, he thought that using only the left hand brought him closer to the original. What is your view on the ‘one-armedness’ of this piece?

– One of the most dramatic features of the Bach Chaconne is the tension between the limiting medium of an unaccompanied violin and the fullness and majesty of the musical content. I believe that Brahms’s arrangement preserves it wonderfully. In my opinion, this tension is lost in Busoni’s lush transcription, though admirable in many other ways. The letter to Clara Schumann which he sent together with the score of his arrangement is so wonderful that I would like to quote it here in its entirety:

“Dear Clara,

I would like to believe that I have not for a long time sent you something as enjoyable as I do today—if your fingers can endure the pleasure! The chaconne is for me one of the most wondrous, most unfathomable pieces of music. On one staff, for a small instrument, the man writes a whole world of the most profound thoughts and the most powerful feelings. If I were to imagine that I could have made, could have conceived the piece, I know for certain that the overwhelming excitement and shock would have driven me crazy. If one has no great violinist at hand, it is the most beautiful pleasure to simply let it sound in one’s mind.

But the piece entices one to occupy oneself with it in every way. One does not always want to hear music sounding just in the air, Joachim is not often there, one tries it this way and that. But whatever I try, orchestra or piano — for me the pleasure is always spoiled.

Only in one way, I have discovered, can I create for myself a very reduced but approximate and completely pure pleasure in the work—when I play it with my left hand alone! Sometimes the story of Columbus and the egg even occurs to me! The similar difficulty, the kinds of technique, the arpeggiating, everything comes together so that—I feel like a violinist!

Try it out, I wrote it down just for you. But: do not overwork your hand! It demands so much sound and strength; play it mezza voce for a while. And make the chords manageable and comfortable for you. If it doesn’t overwork you—which I believe it may, however—you should have a great deal of fun with it.”

Brahms: Variations and other works – listen to excerpts

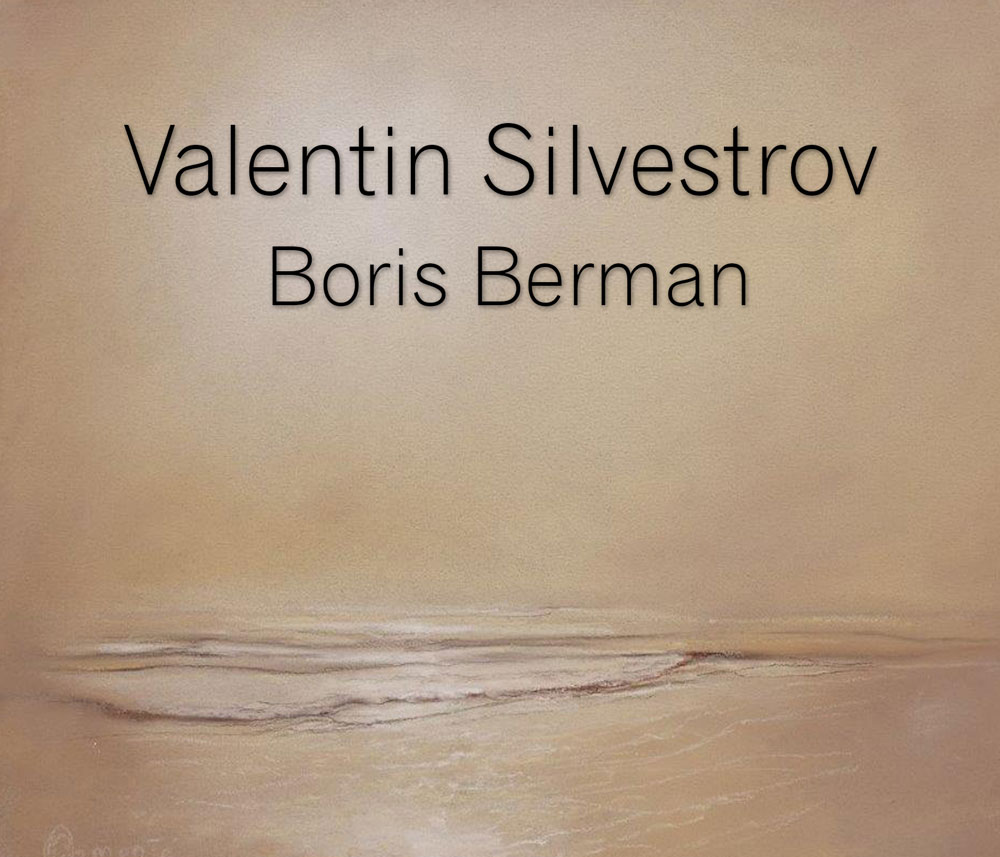

Valentin Silvestrov: Piano Music

Valentin Silvestrov was born in Kyiv, Ukraine, in 1937. His music has evolved from an assertive avant-garde – earning him the wrath of the Soviet regime – to a peaceful, intimate, melodic, and tonal style. Since 2001, he has composed a multitude of short pieces, forming a “bagatelle epic”, which consists today of more than 300 opuses. When Russia started its invasion of Ukraine, the 85-year-old composer yielded to the pleas of friends and relatives and left Kyiv – where he had lived all his life – reaching Berlin after a perilous journey by car.

Boris Berman is bound to Silvestrov by a friendship that started at the beginning of the 1960s, when they were both Soviet citizens, and Berman performed the composer’s early Triade. When embarking on an international career that has taken him to all continents, Berman continued to promote Silvestrov’s work. He is pleased that Silvestrov is now played more often, but would like to address the fact that people seem to turn almost exclusively to the late pieces. In order to present a more complete picture, Berman’s album, due for release in November, offers a panorama of Silvestrov’s evolution during the past six decades, including the premiere recording of Three Pieces written in Berlin in March 2022.

– You have known Silvestrov for 60 years and you obviously appreciate both his early and new styles. What actually happened when he abandoned his modernist way of composing?

– This is true, I appreciate both his early and new styles. I feel that ignoring his earlier works makes him a much smaller figure, a mere ‘new age’ composer. Silvestrov himself sees a connection between his avant-garde works and the late ones. I wonder if Silvestrov himself realized that he was making a stylistic turn: let us not forget that after Kitsch Music written in 1977 in the “new” euphonic style, he wrote the modernist 3rd Sonata (1979). It seems that it started as another experimental foray into a new territory, which appeared to open new horizons for him. These are Silvestrov’s own words about the relationship between his avant-garde and latest works: “This was not a break but a transition. In pieces composed after the 1960s, the avant-garde did not disappear, but simply moved ‘backstage’ and permeated the musical texture from within like a grain of salt. The technique of the composer works in a hidden way in the realm of the unseen and unheard. This humility creates its own inner tension.”

– How would you describe Silvestrov’s late style? What is it that he is trying to achieve through his endless stream of introverted “bagatelles”?

– Silvestrov’s style of recent years is lyrical, intimate, and introverted. We can call it nostalgic insofar as it tries, somehow, to awaken his memory – that of his music, that of his life. It’s about the nostalgic attempt to unify life into a whole, which is of course impossible because life goes on and the past cannot return. It’s related to what Proust did in his colossal In Search of Lost Time, but Silvestrov tries to achieve the same thing through pieces lasting two to four minutes.

– Recently, you have given several recitals playing Brahms and Silvestrov side by side. Do you see any connections between the two?

– I do feel the affinity between Silvestrov and Brahms, both have this special quality of nostalgic introverted understated lyricism. Silvestrov himself pointed out to me the connection between the third piece of his Kitsch-Musik and Brahms’s E flat Major Intermezzo op. 117 No. 1. On the other hand, the robust impulsivity of the early works of Brahms on my program adds a welcome contrast.

Boris Berman on Valentin (Valentyn) Silvestrov’s music

Boris Berman performs Silvestrov Triade (1962) and Kitsch Music (1977):

Valentin Silvestrov: Piano Music (release in November 2022)

Triade (1962)

Elegy (1967)

Sonata 2 (1975)

Sonata 3 (1977)

Kitsch-Musik (1977)

Postludium op. 5 (2005)

Five Pieces op. 306 (2021)

Three Pieces (March 2022, Berlin)

(Palais des Dégustateurs PDD030)

Berman’s recordings for Le Palais des Dégustateurs can be ordered from UVM Distribution

Brahms: Variations / Boris Berman

Brahms: Klavierstücke / Boris Berman

Brahms: Sonatas Op. 120 and Trio Op. 114 pour Alto

Debussy: Préludes, Estampes & other pieces / Boris Berman

Haydn – Schubert: Sonata in E flat Major, Hob. XVI:52 and Sonata in A Major, D. 959 / Boris Berman

Further reading about Berman on Piano Street:

The Art of Listening — Updated Notes from Berman’s Bench

Prokofiev’s Piano Sonatas – A Guide for the Listener and the Performer

Pingback: Le piano de Boris Berman à découvrir et savourer dans Silvestrov et Brahms - Alain Gandolfi Studio Mobile